It has just come to my attention that this month marks 30 years since the Morris brand was axed* by British Leyland. In a pleasing historical quirk this year is also the centenary of Morris Motors and I couldn’t let a double anniversary like that pass without comment.

It’s no easy task deciding which of its brands British Leyland managed to screw over most thoroughly (I’ll save that debate for a future post or several) but I’ve long had a suspicion that Morris was the most undeserving of being dragged through the mud to the extent that it was.

Back in 1982 the Morris badge was last seen gracing the tailgate of this example of British automotive workmanship:

The Ital was a facelifted version of the Marina Mark 2, which was in turn a lightly facelifted version of the original Marina which was launched back in 1971. It was a half-hearted attempt by BL to string out the one remaining Morris product for a few more years until the entire company would be saved by the Austin Maestro. An infallible plan if ever there was one.

The Ital was just the last of many automotive insults directed at Morris over the years, and I mean insult in a fairly literal sense. You see British Leyland were generally useless at consistent brand strategies but they and their predecessors managed to wage a pretty consistent war against Morris. As conspiracy theories go it’s not a very good one, although I kinda want to see the Hollywood blockbuster version – The Issigonis Code, where an innocent motoring journalist tears around the West Midlands by night trying to unearth the terrible secret of Britain’s industrial past whilst being pursued by sinister agents from BMW.

Where was I? Oh yes. Morris.

As any fool knows, one of the core strategies that British Leyland had to deal with its minestrone of brands was that cars designed around their innovative front-wheel drive layout and fluid-based suspension systems would be Austins whilst the Morris name would be used on conventional rear-wheel drive cars with conventional live axles, conventional leaf springs and conventional styling. Fair enough, you’d think – BL were canny enough to realise that a lot of people, especially company fleet buyers, didn’t trust that fancy hydro-thingy-ma-gubbin suspension and BMC’s previous attempts to sell radical cars in the upper parts of the market (the Glorious Landcrab) had failed precisely because they were radical.

But why were the brands split along those lines? Did Austin have a reputation for engineering innovation that Morris didn’t? The answer is no. It was, if anything, the complete opposite.To fully appreciate BL’s wrongness we need to go back to the start of things.

William Morris (the car guy, not the designer of floral wallpaper) was a latecomer to the motor industry. He didn’t set up shop in Oxford until 1912. He hit on the idea of building his cars almost entirely from parts bought in from other companies. This led to the first of the famous ‘Bullnose’ Morrises and it meant they could be keenly priced, to the extent that Morris was able to gradually buy out all his suppliers at zero expense to himself. Morris then founded what would go on to become the keystone in the whole British Leyland mess, Pressed Steel, becoming the first car builder outside America to make cars entirely from (guess what?) pressed steel panels.

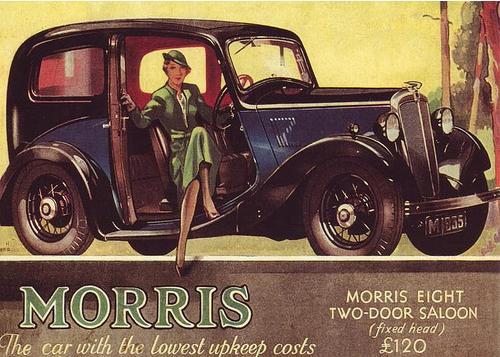

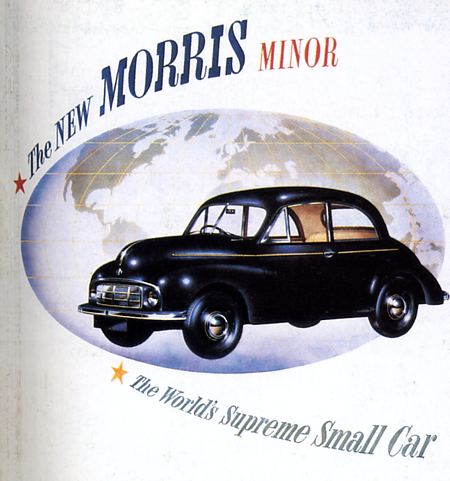

Spurred on by the success of Austin’s ‘baby’ Seven Morris launched the Minor in 1928, the first car to sell for £100. This was complimented by the Eight which sold so well that Morris was able to overtake Austin as Britain’s biggest car maker. The later ‘E Series’ version of the Eight introduced semi-streamline styling and faired headlamps. After war, with egotistical genius Alec Issigonis in charge of the design office, Morris produced the next generation of the Minor which was arguably Britain’s first ‘modern’ family car, with rack-and-pinion steering, torsion bar suspension, monocoque construction and up-to-the-minute styling. It was Issigonis, of course, who in later years would produce all the genuinely radical features that BL would decide to put on Austins.

In all this time Austin hadn’t been slouching but they hadn’t done anything really innovative since the launch of the original Seven in 1922. They were utterly conventional, mass-market cars built down to a price and they were very good at being so.

In all this time Austin hadn’t been slouching but they hadn’t done anything really innovative since the launch of the original Seven in 1922. They were utterly conventional, mass-market cars built down to a price and they were very good at being so.

We shouldn’t forget that Morris spawned MG (Morris Garages) along the way, thus setting up another national motoring institution.

So why did BL pitch Austin as its ‘white heat of technology’ brand? Because BL, or more accurately the Austin-Morris division of BL, was run by Austin men some of whom didn’t just view Morris as a former rival but actively disliked the company and its people. The Austin v. Morris rivalry was a very personal thing as corporate rivals could be back in the days when companies were run by one man whose name was on the factory gates.

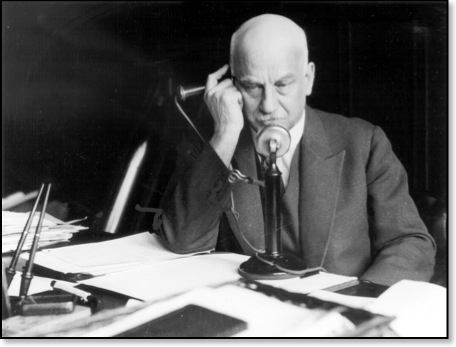

It started back in the 1920s when Herbert Austin and William Morris were going head-to-head in the British car market. Both wanted to buy the ailing Wolseley company, where Herbert had got his big break in the industry as managing director when it was founded. Bill wanted it because Herbert wanted it, and he wanted it more. Herbert never forgave Morris for stealing ‘his’ company and this attitude filtered down to the rest of the top-brass at Longbridge

Herbert Austin- the first victim of a sniping bid?

Herbert Austin- the first victim of a sniping bid?

Ten years later William Morris finally fell out with his General Manager, Leonard Lord, after many years of ‘differences of opinion’ and he found a warm welcome at Austin. So now the two biggest car companies in the country were both stacked full of people who hated each other.

Which wasn’t going to end well when the two companies were ‘encouraged’ to merge by the government to remain competitive in the global industry and formed the British Motor Corporation. Leonard Lord was the first chairman, the corporate headquarters was at Longbridge and the majority of the design and engineering work was moved there too (ever wondered by all the BMC models had ADO [Austin Drawing Office] designations?). Lord was suceeded by George Harriman, who had been his Number Two at Longbridge and was another Austin Man. The attitude, at Longbridge at least, was that BMC was an Austin-led enterprise.

So that’s why, despite all the evidence, Austin was Leyland’s ‘preferred’ brand. Of course, I’m not saying that BL purposely made the Marina rubbish so it wouldn’t sell – that wouldn’t have been in their interests and it was hardly as if the Austin products were all wonderful to put the Morris ones out of the game.

BUT…who had the last laugh?

When the Morris brand was snuffed out in ’82 what stepped in to fill the void? The Maestro and Montego, which were conventional, rather boring cars. They also had named beginning with M, and doesn’t ‘Morris Montego’ have a much better ring to it? When the sporty versions were released they were badged as MGs. The Austin brand was itself ditched just 7 years after its arch rival.

Today half of Longbridge has been demolished and the remaining half is hardly a thriving industrial concern. It’s also owned by MG, a Morris brand. The company that owns it actually uses the Morris Garages name in its home market of China.

The actual Morris factory at Cowley and its neighbouring Pressed Steel plant is full to capacity churning out MINIs, with all its Issigonis heritage. And where does the MINI name come from? It was from the name given to the Morris versions of Issigonis’ masterpiece, the Morris Mini-Minor.

I think, in the end, William Morris can have the last laugh.