Following on from last week’s blog, here are the final three entries in my list of cars that would have been much better had it not been for what was under the bonnet.

1) Rover ‘R3’ 200

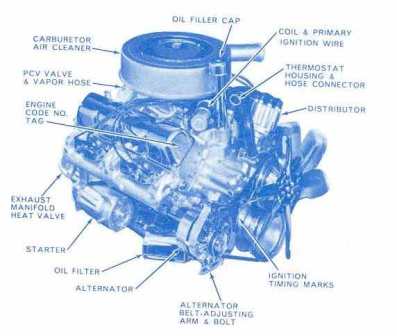

Is that bonnet open? Seriously- is that bonnet open??

Is that bonnet open? Seriously- is that bonnet open??

I could have populated this entire list with Rover Group cars that had the misfortune to be fitted with the K-Series engine in its original form because all of them suffered from the engine’s unfortunate and infamous head-gasket problems.

However I happen to believe that the car most cruelly denied deserved success by the ‘Kettle Series’ was the R3 200 series. The MGF and the Freelander managed to become best-sellers in their respective class despite the engine and the Rover 45 and 75 had more general marketing problems that made the engine largely irrelevant.

The R3 should have done better than it did. It was the first all-Rover car since the Montego (and would go on to have the unenviable distinction of being the last wholly indigenous UK-designed-and-built mass market car) and had to replace both the R8 and the aging Rover Metro. As such it was a rather odd size, straddling the supermini and small family car segments.

The R3 followed the same pattern as the R8 and was priced at a similar level to the higher specifications of Ford Escort and Vauxhall Astra but being much more modern in design and engineering with far superior handling, better refinement and a veneer (literally) of old-world Rover wood-and-leather charm that justified its price premium to many buyers. Following the pattern established by the Montego and the R8 the new 200 eschewed the weird suspension and odd styling of the older BL cars and reaped the benefits of being conventional but well sorted and effective. It still couldn’t compete with Volkswagen and BMW on quality and fit/finish but it didn’t cost nearly as much.

The problem, of course, was the engine. The K-Series had been very well received on its debut in the R8. Its advanced all-alloy single casting construction, modular top end design and extremely low weight made it efficient, free-revving and bestowed sharp handling on the cars it was fitted to. Rover’s Variable Valve Control system was second only to Honda’s VTEC system for producing fast-revving, powerful engines and had the benefit of producing an almost entirely flat torque curve.

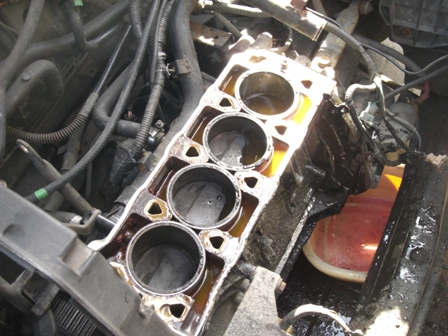

It’s really hard to find pictures of K-Series engines in one piece, so here’s one in its natural state.

It’s really hard to find pictures of K-Series engines in one piece, so here’s one in its natural state.

Unfortunately by the time the R3 came along the K-Series had been redesigned to be produced in higher capacities. Originally available in 1.1- and 1.4-litre versions the second generation was also produced in 1.6- and 1.8-litre capacities and to do this the top deck of the engine was removed to make it an unusual ‘very wet liner’ design. This placed undue stress on the head gasket which, as we all know, failed with alarming speed and regularity. The bigger versions gave the sporting R3 200s rapid performance but all were afflicted with HGF problems which would occur almost perfectly on cue at 60,000 miles or so.

The K-Series’ well publicised problems (and Rover’s reluctance to do anything about it) overshadowed all the company’s products but the R3 was cruelly denied the success that its otherwise sound and reliable design deserved. The fact that the versions fitted with the bombproof L-Series diesel remain popular and desirable today while petrol-engined versions are hard to give away.

2) MGC

Top of the list of Things That Could Make an MGB better- a power bulge in the bonnet.

MG was on something of a high in the 1960s. The MGB had been launched to great acclaim and success worldwide, the evergreen Midget cars were selling well and the brand as a whole was safely on its way to becoming, by the early 70s, the third most valuable brand in the world.

The problems were one of power and one of politics. The power problem was the MGB’s B-Series engine. At 1.8 litres it had reached the limits of its development potential and even with twin carbs and a sharp camshaft it only produced 95 horsepower. That was fine for zipping around British B-roads on a summer’s day but when laden with anti-smog gear for the crucial American market this figure dropped to a distinctly anaemic 75 horses.

At the same time MG’s corporate parent, BMC, was feeling the loss of the ‘Big Healey’ model, the 3000 MkIII. The Austin-Healey brand had been dropped because it made no sense to maintain two separate sports car lines in the same company. However MG had nothing to directly replace the hairy-chested Healey.

The solution seemed obvious- put the engine from the Healey in the MGB. Not only would this solve two problems but the big-engined MG would be available in GT form, something the Healey never was. This created the prospect of a cut-price BMC equivalent to an Aston Martin.

Unfortunately the engine in question was the BMC C-Series 6-cylinder. This came courtesy of Morris (unlike the other two BMC power units) and had its origins as the propulsion for the big Morris land-yachts such as the Isis and the Wolseley 6/90. It was a big, heavy, iron engine for big, heavy iron cars.

Unfortunately the engine in question was the BMC C-Series 6-cylinder. This came courtesy of Morris (unlike the other two BMC power units) and had its origins as the propulsion for the big Morris land-yachts such as the Isis and the Wolseley 6/90. It was a big, heavy, iron engine for big, heavy iron cars.

BMC actually spent a great deal of money redesigning the C-Series for use on the MGC and their proposed luxury saloon, the Austin 3-Litre. Although using the same core dimensions the new version was narrower and slightly shorter than the original engine and it had 7 main bearings.

As in the Austin-Healey the C-Series in the MGC (as it was inevitably called) had twin SU carburettors but the MG version had to use slightly smaller units running at a lower tune for packaging and safety reasons. The real problem was one of weight. The C-Series weighed in at 240 kg and all that added weight had to go over the nose of the MGB, never a car that needed making more nose-heavy than it already was.

The result was that the MGC’s handling had none of the quick-fire ‘chuckability’ of the MGB and none of the raw and slightly fearsome waywardness of the big Healey. Similarly the B-Series may not have been a fire-breathing powerhouse but it was engine that enjoyed a good thrash and made a decent noise. The C-Series, especially in the tune used in the MGC, was more for refined wafting than thrashing. The MGC in its original form was just a wallowly, badly-balanced mess with all the fun taken out of a car that built its entire brand on just that. BMC wisely killed it off after 2 years.

3) AMC Pacer

I am now going to do something deeply unfashionable and say slightly complimentary things about the AMC Pacer, ‘America’s Allegro’. Widely regarded as one of the worst cars ever made it was so monumentally awful that even Americans in the 70s spurned it, and if you look at some of the cars Detroit was rolling out in that decade you’ll realise that their standards weren’t high.

However, rather like the Citroen DS that made the list last week, the Pacer is a car which never fully realised its designer’s potential because it had a fundamentally unsuitable engine

However badly wrong the execution was, the Pacer was a brave attempt to do something different, which should always be admired. The American motor industry went into something of a panic after the 1973 Fuel Crisis when the public suddenly began caring about fuel consumption. The major companies responded in different ways. General Motors ignored the problem entirely and launched a Cadillac Eldorado with an engine capacity equivilant to that of nine Morris Minors. Chrysler hastily called up their subsidiary in England and slapped the Plymouth badge on a Hillman Avenger. Ford took one of their European engines and put it in an American-designed car that became famous for self-combusting in a crash.

Only AMC had what could be termed a decent idea. As the fourth entrant in the three-player game that was the US car market AMC had been used to thinking outside the box and had carved out a niche of lower-end products such as Rambler Station Wagons and the famous Gremlin ‘wedge car’ which were combined with clever marketing to pitch them as youthful anti-establishment products with features such as interiors clad in Levi’s branded denim.

The Pacer was supposed to be an all-American product to give customers what they suddenly wanted- smaller cars that used less ‘gas’. This was also the era of Ralph Nader so the Pacer emphasised urban safety. At the same time it was aimed at people trading down from full-size cars who wouldn’t want to compromise on comfort. This gave the Pacer its odd looks. It was deliberately kept as wide as a normal car but was much shorter. The need for good visibility and a sense of space produced its bulbous windows while an emphasis on low drag for good fuel economy made the external detailing rather bland and plain in comparison to many of its contemporaries. .

The Pacer was also supposed to be clever. AMC had struck a deal with General Motors to buy Wankel rotary engines from them. GM had been one of many companies to believe in the future of the rotary engine and had invested heavily in its development. When they canned their project AMC was left without their rotary engine and no means of developing their own. They fell back on their range of good ol’ iron reciprocating engines designed for station wagons and Jeeps driving a 3-speed slushbox through a live rear axle hung from leaf springs.

The Pacer was supposed to be a ‘form follows function’ sort of design where the odd styling and design quirks meant that it worked better than a normal car. This only works if the function is actually good. Instead the Pacer became a car that looked uncannily like a goldfish bowl on wheels for no real reason. Supposed to be a car for a new, ecological age, its smallest engine was a 3.8-litre six and you could get it with a 5-litre V8 that slurped now-precious fuel at the rate of a gallon ever 13 miles. Burdened down with emissions equipment even the biggest engine produced only 125 horsepower in a 1.3 ton car and the Pacer handled with all the alacrity you’d expect from an American car of its time.

So the Pacer was a compact economy car that turned out to be a large, ugly, thirsty, slow and squidgy car. I can’t imagine why it didn’t succeed.

And no, I’m not going to mention the Triumph Stag on this list. That’s far too obvious!