Usually the tone of my road tests are defensive, taking the tone that ‘[car’s name] may have been a sales flop and generally seen as rubbish, but it must have some redeeming features’. In this case though the subject of this ‘Let’s Go For A Drive’ is an undeniably good car – one that garnered praise from the press at its launch and which topped the UK sales charts for cars of its type for nearly a decade. I refer, of course, to the MGF roadster.

Usually the tone of my road tests are defensive, taking the tone that ‘[car’s name] may have been a sales flop and generally seen as rubbish, but it must have some redeeming features’. In this case though the subject of this ‘Let’s Go For A Drive’ is an undeniably good car – one that garnered praise from the press at its launch and which topped the UK sales charts for cars of its type for nearly a decade. I refer, of course, to the MGF roadster.

Now, as good as the MGF undoubtedly is, it is not without its issues and it’s reputation is not unsullied. As well as the standard-issue reliability issues with its K-Series power unit there is the fact beloved of the pub bore – “it’s just a back-to-front Metro”. This is true. It also has Hydragas suspension and, for all that system’s many advantages ‘sportiness’ is not one of them.

So these are my thoughts after driving an MGF for the first time. What is it about the little MG that made it such a success? Can a car based on another car running backwards really be that great a drive? Read on and find out.

Outside

The F was MG’s first all-new car since the launch of the MGB roadster back in 1962 and was also the first bespoke MG car since the B had ceased production in 1980. Add to this that the F was MG’s first rear-engined car it was clear that it had very little in common with any previous MG product. The styling bares this out. Nothing about it really says ‘MG’. The styling is very 1990s with smooth lines and rounded detailing. Despite the wholly different mechanical layout the F manages the same largely symmetrical, balanced look as the older MG roadsters without any of the tail-heavy wedginess that some rear-engined cars end up with. There are a few stylistic hints from MGs of the past, with the front bonnet and wheelarches lifting up into ‘wings’ behind the headlamps like the MGB and the two-part ‘moustache’ grille is also an MGB carry-over. All the same the F isn’t a retro product. These cues are very subtle and are in many ways overshadowed by the F’s own styling such as the big rear light clusters and the air intakes behind the doors which are blended into a big styling crease down to the sills. The car sits low to the ground, as you’d expect from a car with sporting pretensions and its short wheelbase and wide track give it a purposeful, planted look. Overall the styling is neat and wholly inoffensive. The MGF isn’t an especially beautiful car but equally there’s nothing wrong with it either.

The F was MG’s first all-new car since the launch of the MGB roadster back in 1962 and was also the first bespoke MG car since the B had ceased production in 1980. Add to this that the F was MG’s first rear-engined car it was clear that it had very little in common with any previous MG product. The styling bares this out. Nothing about it really says ‘MG’. The styling is very 1990s with smooth lines and rounded detailing. Despite the wholly different mechanical layout the F manages the same largely symmetrical, balanced look as the older MG roadsters without any of the tail-heavy wedginess that some rear-engined cars end up with. There are a few stylistic hints from MGs of the past, with the front bonnet and wheelarches lifting up into ‘wings’ behind the headlamps like the MGB and the two-part ‘moustache’ grille is also an MGB carry-over. All the same the F isn’t a retro product. These cues are very subtle and are in many ways overshadowed by the F’s own styling such as the big rear light clusters and the air intakes behind the doors which are blended into a big styling crease down to the sills. The car sits low to the ground, as you’d expect from a car with sporting pretensions and its short wheelbase and wide track give it a purposeful, planted look. Overall the styling is neat and wholly inoffensive. The MGF isn’t an especially beautiful car but equally there’s nothing wrong with it either.

Like all the best British sports cars you have to lower yourself into the MGF’s cabin and once the door closes it feels cosy and cockpit-like, which is how it should be. If you’re at all familiar with Rover Group products of the 1990s you’ll immediately start noticing all the parts-bin switches, dials and panels, most of which seem to have come from the R3-type Rover 200. The inside is more consciously retro than the outside, with cream leather seats, steering wheel cover and gear lever gaiter, as well as black-on-beige dials and ‘wooden’ surrounds on the heater vents and switch panels. The MGF is certainly better ergonomically than any previous MG roadster. You sit low, in the classic ‘backside on the ground’ pose familiar to any MGB driver, but the seats are comfortable and supportive. The steering wheel is near-vertical and, although it is simply the Rover Group standard-fit one of the time it feels right. The gauges (speedo and rev counter flanked by smaller fuel and temperature dials, just like any other Rover product of the era) are clear . The centre tunnel and console is raised up a little compared to a normal car which helps add to the cockpit feel. The view out the front is very good. The lack of an engine in the front means the bonnet slopes continually away from the windscreen leaving very little of the car visible to the driver despite the low seating position and rather giving the impression that you’re strapped to the very front of the vehicle. The only other dials are a clock and an oil temperature gauge above the radio. I suppose the oil temperature gauge adds a certain hint of performance.The only quirk is the presence of a button for a heated rear windscreen, which baffles me slightly because this car has a hood, with an unzippable plastic rear window.

. The centre tunnel and console is raised up a little compared to a normal car which helps add to the cockpit feel. The view out the front is very good. The lack of an engine in the front means the bonnet slopes continually away from the windscreen leaving very little of the car visible to the driver despite the low seating position and rather giving the impression that you’re strapped to the very front of the vehicle. The only other dials are a clock and an oil temperature gauge above the radio. I suppose the oil temperature gauge adds a certain hint of performance.The only quirk is the presence of a button for a heated rear windscreen, which baffles me slightly because this car has a hood, with an unzippable plastic rear window.

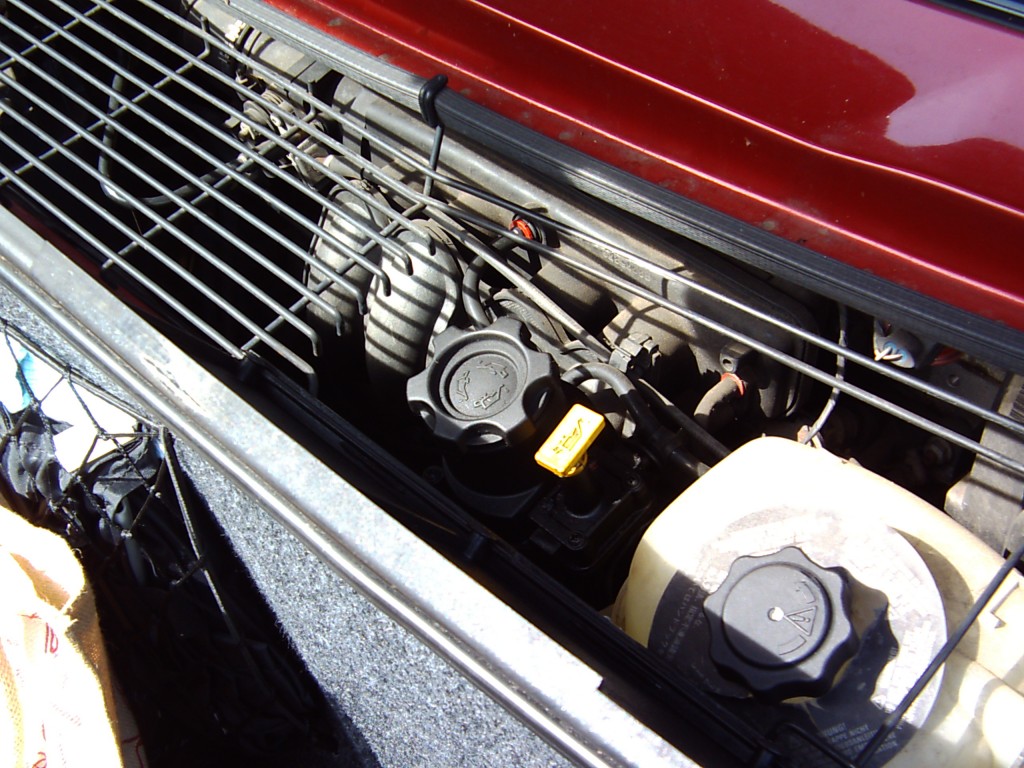

Being mid-rear engined the MGF has a ‘boot’ in the back and a ‘sort of boot’ in the front. The release handle for the latter is located inside the former, which left me resorting to the handbook (horror!) to find out where it was. The boot proper is a decent size with a large opening and does rather leave you wondering where the engine is, since it seems to back straight onto the cabin. In fact the engine lurks under a series of removable grille panels at the front of the boot. You can just about see the oil filler, dipstick and coolant expansion bottle but apart from a restricted glimpse of the familar twin cam K-Series top cover you can’t see anything else.

Under the ‘bonnet’ is the spare wheel, battery and brake master cylinder, which is on the opposite side of the car to the controls.

Under Way

The MGF’s key is an octagonal variant of the famous Rover ‘bendy key’. Turn it and the 1.8-litre K-Series fires up quickly (incidentally the K-Series’ capacity is within a few ccs of the capacity of the B-Series unit found in the MGB). It’s a little strange to hear all the engine noises coming from behind. The engine breathes though two fairly short exhaust pipes and these, coupled to the usual K-Series fast idle when cold produce a very MG-like raspy noise. Otherwise the engine is smooth and refined and there is very little in the way of vibration and no rattles or squeaks. Very un-MG-like.

It’s a shame that Rover didn’t try and fettle the gearchange a little for their new baby sports car. The standard K-Series/Honda gearbox combo shift is by no means bad but one of the joys of the old MGs was their tight, narrow-gate gearbox with an action that was both slick yet offered just enough feedback to be satisfying. The F’s gearchange is nothing special although it is a little on the heavy side and does feel as if its actually connected to something.

The MGF in this test is a very early Mk1 example. Thus it is in many ways the ‘purest’ in the classic MG sense. Whilst later or higher-specced Fs had more powerful engines with Rover’s VVC system or the Tiptronic CVT this one has the basic 118 horsepower engine and a 5-speed manual gearbox. This bodes well because classic British roadsters were never about outright performance. They were about making a lot of noise, feeling as if they were going a lot faster than they actually were, an involving driving experience and handling that was sharp and quick even if it wasn’t particular good.

K-Series engines without VVC were never particularly strong on low-speed torque and this one is no exception. You need a fair amount of revs in hand to pull away and the initial take-off doesn’t overwhelm you with speed. However the engine is very free revving and offers more the more you ask of it. Keep the revs up and don’t be afraid to work the engine hard and it delivers a very ‘sporty’ experience. The official 0-60 time of 8.5 seconds isn’t great by modern standards and my time with this F made it seem rather optimistic as the car is nippy rather than properly quick. However these cars are all about the experience and the F delivers in spades. Although the engine is only a few inches away from your ears it doesn’t make too much noise, especially when driven normally, other than a slightly coarse note as you’d expect from a wide-bore 4-cylinder. However when you open the taps you get an earful of exhaust rasp, a pleasant amount of induction roar and, at the higher engine speeds, a smooth, purposeful whine. It’s not the same flatulent, ‘rorty’ noise of an MGB or a Midget but it’s engaging.

When not being a sports car the MGF is perfectly happy. Once moving the engine is tractable enough and it has good mid-range poke. It’s a very easy car to drive normally, which is something a lot of cars with performance design briefs don’t manage very well. The cabin is well insulated from the engine and the road and the soft top is free of excessive wind noise and draughts. The best bit is making the transition between the two ‘modes’. The fact that the F has slightly blunt performance means that you can enjoy the odd wide-open-throttle moment (those tempting 30-to-National Speed Limit changes, for example) without instantly finding yourself the wrong side of the law.

When not being a sports car the MGF is perfectly happy. Once moving the engine is tractable enough and it has good mid-range poke. It’s a very easy car to drive normally, which is something a lot of cars with performance design briefs don’t manage very well. The cabin is well insulated from the engine and the road and the soft top is free of excessive wind noise and draughts. The best bit is making the transition between the two ‘modes’. The fact that the F has slightly blunt performance means that you can enjoy the odd wide-open-throttle moment (those tempting 30-to-National Speed Limit changes, for example) without instantly finding yourself the wrong side of the law.

Ride and Handling

This is where the MGF really has to shine because, as mentioned, a British sports car is all about the driving experience rather than the actual performance.

The key issue to address is the Hydragas suspension. Anyone who’s seen an Austin Allegro or a Princess bounce and roll its way along even a slightly undulating road will wonder at the sense in putting the system in a sports car. However the point of Hydragas was that it offered a highly compliant ride whilst still allowing good, safe handling. It was also ‘tuneable’ simply by fitting the system with displacer units of different capacities, fluid/gas ratios and fluid restriction. In the MGF the emphasis has, clearly, been placed on handling rather than ride comfort. If you didn’t know I don’t think you’d be able to tell that the F had anything other than conventional suspension most of the time. The ride is certainly good but it is not exceptional. Rough road surfaces, bumps and potholes cause the odd jar and thump but the structure of the car is well insulated from the suspension and it takes a serious defect in the road surface to actually became unpleasant.

Where the Hydragas really shines is in the car’s stability. Cars with short wheelbases are usually skittish, especially when fitted with firmer suspension in search of good handling. With independent but interconnected suspension at each corner the MGF is fantastically stable and planted. As intended the interconnection completely kills any pitching which is the traditional bete noir of short wheelbase vehicles. At the same time the stiffer ‘spring’ rates combined with anti-roll bars mean that roll is also kept to a minimum and even the worst that Hampshire’s back-roads had to offer in the way of a corner, camber, incline and a mid-turn bump couldn’t faze the system and the MG kept tracking straight and true. At the other end of the scale the car also remains rock solid at motorway speeds with no need to constantly tweak the steering and no jumping buffeting when you hit a crosswind or the bow-wave of an HGV. The result is a car which is perfectly comfortable and easy to drive normally which can also turn in a grin-making performance if you decide to ‘make decent progress’ over a fast and twisty road, especially as you can maintain a fast but legal speed where a less sweet-handling car would have to slow down.

Where the Hydragas really shines is in the car’s stability. Cars with short wheelbases are usually skittish, especially when fitted with firmer suspension in search of good handling. With independent but interconnected suspension at each corner the MGF is fantastically stable and planted. As intended the interconnection completely kills any pitching which is the traditional bete noir of short wheelbase vehicles. At the same time the stiffer ‘spring’ rates combined with anti-roll bars mean that roll is also kept to a minimum and even the worst that Hampshire’s back-roads had to offer in the way of a corner, camber, incline and a mid-turn bump couldn’t faze the system and the MG kept tracking straight and true. At the other end of the scale the car also remains rock solid at motorway speeds with no need to constantly tweak the steering and no jumping buffeting when you hit a crosswind or the bow-wave of an HGV. The result is a car which is perfectly comfortable and easy to drive normally which can also turn in a grin-making performance if you decide to ‘make decent progress’ over a fast and twisty road, especially as you can maintain a fast but legal speed where a less sweet-handling car would have to slow down.

The steering also plays a big part in this. It’s a traditional rack-and-pinion setup with electric assistance (rather innovative for the time!). The first thing that struck me was the weight of the steering as for a PAS system its quite heavy. Heavy may not be the right word, perhaps ‘weighted’ would be better. It’s also nicely progressive being responsive without being twitchy. The hefty feel to the steering really makes you feel like you are ‘working the car’ and removes the sense that the car is largely driving itself which I suspect the ride and grip may otherwise make you feel. Given the reputation EPAS has for killing any feel or feedback the system on the MG is very good.

Classic MGs were always rather tail-happy on a wet road if they were provoked. This was part of their appeal- whilst quite safe and easy to drive most of the time if you mashed the accelerator enough on a damp day you could get a little controlled tail slide. I was expecting the MGF, being a modern, safe and predictable car, to not have any such vices. I was surprised (in both the good and bad senses) when I went around a roundabout on a drizzly afternoon and with a little groan from the back wheels the rear end swung out. It was by no means dangerous or excessive- the back wheels just got slightly out of line and it could easily be corrected with the steering but it showed that the MGF wasn’t an entirely compliant car and I’m sure that someone more nerve and driving skill than myself could get a lot more in the way of sideways action from it.

Conclusion

It’s very clear why the MGF was such a hit. Whilst owing almost nothing in terms of styling or mechanics to its predecessors it is very much a ‘proper’ MG with focus on the right areas. It’s not a particular fast car but it excels in providing an entertaining experience. It’s simply a fun car to drive, and that’s what MGs were always about. At the same time it’s a practical, comfortable car that’s easy to use on a day-to-day basis. What the MGF really demonstrates is how good Rover was at ‘making do’. Yes, it uses Metro subframes back to front and yes, it has a suspension system from the 1970s that was never intended to be used on a sports car, and yes, the interior is almost entirely built out of bits of other cars but none of this matters. The MG is much more than the sum of its parts and it shows the ability of Rover to fettle a car to bring out its best which would later come to the fore in the MG ‘Z-cars’ of the 2000s. At the same time the F encapsulates everything an MG roadster should be, which is mainly a car which is fun above all else. Here’s hoping that the current incarnation of the company can do as good a job when they turn their hand to a 21st-century MG sports car in the future.