I make no bones about being an enthusiast of British Leyland cars. Been there, done, that, literally got the T-shirt. Being a BL fan is one of those things that society at large generally treats with a certain element of sympathetic contempt (like smoking, The Independent or musical theatre). That’s fair enough, really, and I’m happy to let the vast majority of the population who don’t get the joy of cars with square steering wheels drive their Audi A3s in peace. It takes all sorts etc.

The problem comes when I end up disagreeing with people who really do put the ‘fan’ in ‘fanatic’. The sort of people who will argue long and hard that the decline of the British motor industry had everything to do with anything other than the cars themselves.

I would describe myself as a ‘BL Realist’ rather than a ‘BL enthusiast’. Actually, I wouldn’t, because that would be a stupid thing to say in any real-world situation, but for the purposes of this blog it will make the point. I don’t think everything that bore the Flying Plughole was a work of genius let down only by some other poor chance of fate. A lot of it was much better than its general reputation deserves. A lot of it really is as bad as it’s made out to be, if not much worse.

A lot of people out there don’t seem to realise this, and this is the sort of thing that I’m getting tired of hearing because it makes me want to go and start enthusing over old Datsuns instead.

1) It was all the Unions’ Fault!!!

This is the standard viewpoint in the snug of the Crank & Tappet Public House. What brought BL down was that its workers didn’t do much work and when they weren’t huddling around a brazier outside Q-Gate or rampaging through Cowley smashing the place up a bit they were half-heartedly slinging cars together so that a fellow down the line could take it apart again for ‘rectification’ while another two blokes stood around and watched, all on cushy wages and jobs-for-life. Alternatively it was down to short-sighted management maintaining a very British air of arrogant apathy that meant that it failed to foresee virtually every motor industry trend between 1965 and 1990 while being more concerned with maintaining its corporate empire than producing a viable industry. The thing is that industrial relations, as the term implies, are a two-way affair.

This is the standard viewpoint in the snug of the Crank & Tappet Public House. What brought BL down was that its workers didn’t do much work and when they weren’t huddling around a brazier outside Q-Gate or rampaging through Cowley smashing the place up a bit they were half-heartedly slinging cars together so that a fellow down the line could take it apart again for ‘rectification’ while another two blokes stood around and watched, all on cushy wages and jobs-for-life. Alternatively it was down to short-sighted management maintaining a very British air of arrogant apathy that meant that it failed to foresee virtually every motor industry trend between 1965 and 1990 while being more concerned with maintaining its corporate empire than producing a viable industry. The thing is that industrial relations, as the term implies, are a two-way affair.

It’s true that the relentless strikes (and the often ridiculous working practises that were put in place by managers who wanted to try and avoid them) caused BL a lot of damage to both its image and its bottom line. The Cowley ‘washing up strike’ in 1983 put a huge dent in Maestro production just as demand was at its height. Cars with a retail value of £100 million (or a third of BL’s big government bail-out) never made it to the showroom because the production lines were stopped.

But the whole of the UK economy was riddled with strikes in the ‘Seventies. Ford and Vauxhall had the same, if not worse, problems and managed to turn out cars that were at the very least semi-decent and profitable. A whole industry can’t be brought down over 53 years simply by its workers going on strike- it takes concerted effort to cock things up in the long term by both parties to do the damage that was inflicted on BL.

2) The public should have been more patriotic!!!

Worst. Excuse. Ever. You can make a case for putting the blame on to almost anyone and anything connected with BL but the car-buying public are the very last people to blame. People should never be expected to use their own cash to buy a clearly inferior product just to prop up an incompetent industry.

Worst. Excuse. Ever. You can make a case for putting the blame on to almost anyone and anything connected with BL but the car-buying public are the very last people to blame. People should never be expected to use their own cash to buy a clearly inferior product just to prop up an incompetent industry.

If anything part of the BL’s problem was that the public were far too forgiving. This isn’t so much a BL-specific issue and more an intriguing insight into the woeful standards of your average car buyer in the ‘Sixties and ‘Seventies, but BMC was quite prepared to keep building the Morris Minor and the Farina saloons because people were quite prepared to keep buying them. It was the car-buying public that let BL ‘get away’ with building the Marina, a thoroughly uncompetitive car that none the less sold over a million examples.

Deliberately-specific excuses aside (“But what if you need to fold the seats down into a double bed!” doesn’t count), can anyone mount a viable excuse as to why Mr and Mrs Average should have bought a Maxi over a Cortina, a Marina over an Avenger or an Ambassador over a Carlton? No.

The general public did, in fact, directly support BL by voting for a series of governments willing to prop the whole creaking edifice up with huge infusions of cash. It rewarded their loyalty by building the Ital.

3) It was all BMW’s fault!!!

Aside from the whole ‘clusterfuck theory’ that I’ve already outlined- that no one entity or event can be blamed for BL’s problems- the hatred for BMW just seems utterly baseless. Yes, BMW screwed up the Rover 75 by making it look like a design from the centre spread of The Eagle, circa 1958 (‘The Car Of The Bank Manager OF THE FUTURE!’) and then using the car’s public unveiling to tell the assembled crowds that Rover was a doomed company staffed by work-shy ne’er-do-wells, but that is more than cancelled out by practically everything else they did.

Aside from the whole ‘clusterfuck theory’ that I’ve already outlined- that no one entity or event can be blamed for BL’s problems- the hatred for BMW just seems utterly baseless. Yes, BMW screwed up the Rover 75 by making it look like a design from the centre spread of The Eagle, circa 1958 (‘The Car Of The Bank Manager OF THE FUTURE!’) and then using the car’s public unveiling to tell the assembled crowds that Rover was a doomed company staffed by work-shy ne’er-do-wells, but that is more than cancelled out by practically everything else they did.

While British Aerospace (who presided over what many would call ‘the glory years’) invested about £7.50 in the Rover Group, the result being the Rover Metro and the Rover R3 200, BMW sloshed millions of its own Deutchmarks into the firm and let them get on with making cars- an approach that the company had desperately needed since the ‘Fifties. The result was the first generation of the MINI, the very successful (if fragile) P38 Range Rover and Land Rover Freelander, the Rover 75 (which under all its pipe-and-slippers styling is an excellent car), the Series II Discovery and the L322 Range Rover.

Leaving aside the issues surrounding BMW’s ditching of ‘The English Patient’, there is the legacy that they left behind. As well as ensuring the continued dominance of Land Rover’s products in the West and the initial success of the MINI, BMW have kept Cowley humming away at full capacity making desirable British-built cars and building engines for the both MINIs and BMWs at Hams Hall. They may have given Rover a further nudge towards its inevitable end but BMW have done more good for the British motor industry as a whole, and especially the remnants of the BL empire, than any of the British owners ever did.

4) But what about the [insert obscure engineering feature here]?!?!?

This is the sort of thing where rational defence starts to tip over into blind ideology. The Maestro was not better than the Ford Escort simply because it was the first car to have a bonded-in windscreen and single-loom wiring. No one cared back in 1980 that the Metro was the first car with 12,000 mile service intervals and no one cares now. The Allegro may have been the first car to have an electric fan, but so what?

This is the sort of thing where rational defence starts to tip over into blind ideology. The Maestro was not better than the Ford Escort simply because it was the first car to have a bonded-in windscreen and single-loom wiring. No one cared back in 1980 that the Metro was the first car with 12,000 mile service intervals and no one cares now. The Allegro may have been the first car to have an electric fan, but so what?

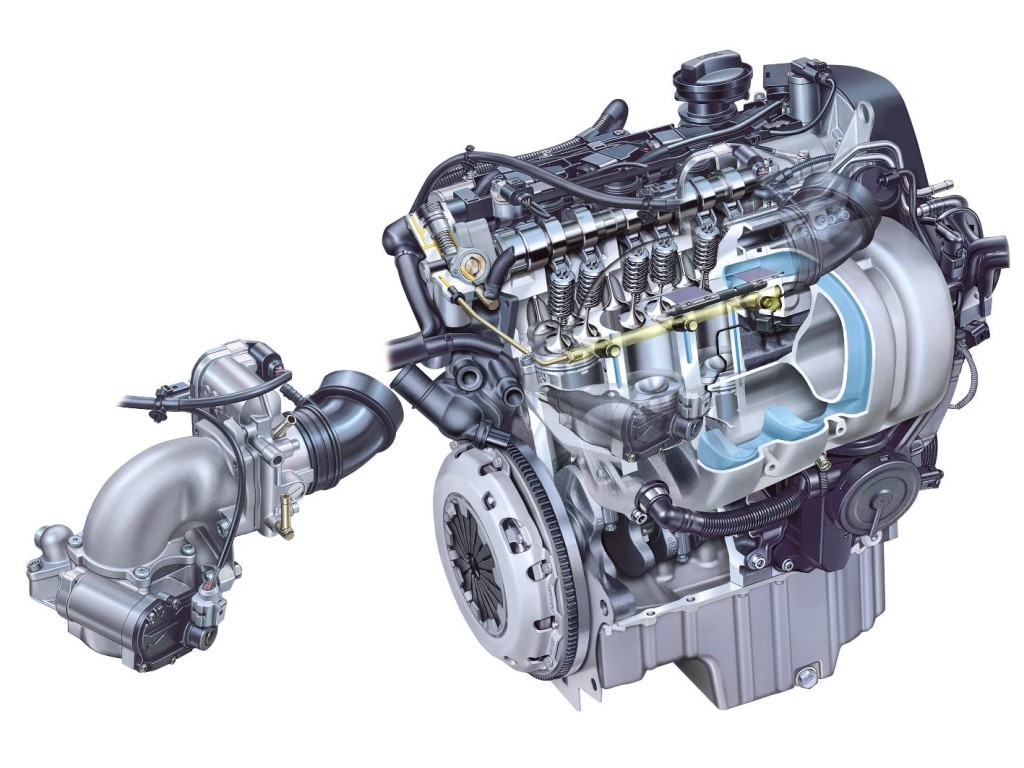

I have, frequently, made the case that BL’s cars are excellent designs but poor commercial products. Fluid suspension may be technically very capable but people didn’t want it. The K-Series engine may be, on paper (or when put in a Lotus) one of the best small-capacity petrol engines ever made but that doesn’t change the fact that it was riddled with detail design and installation errors that all but guaranteed expensive failure.

Even the apparently successful stuff shouldn’t be immune from criticism. How many cars today use the much-hyped Issigonis transverse engine with the gearbox in the sump? None, that’s how many. How many use the transverse engine with the gearbox on the end, as invented by Fiat? Most of them. What was BL’s reaction to this much better way of laying out the drivetrain of a car? To ignore it entirely, try and squeeze five gears into the sump of an E-Series and then, when that didn’t work, buy a proper gearbox from Volkswagen and then somehow cock that up too. How many sales did BL lose because its ‘Issigonis-style’ cars were slow, odd-looking rotboxes with mushy gearchanges and NVH levels similar to a Victorian steel mill? Tens of thousands.

We can always find some metric where a BL car will be superior to a more successful or more highly-though of competitor, or some feature that BL introduced before everyone else, but that doesn’t remove the blame from the company or the car for all the other faults.